The Registry of Standard Biological Parts is a library of DNA sequences combined with online characterization resources. The Registry has created a standard protocol for making segments of DNA compatible with all other segments of DNA, regardless of order or size. BioBrick is the term given to such segments of DNA, a term alluding to the fact that any number of bricks may be combined in any order to produce complex, unique systems. This is accomplished by standardizing the restriction enzymes used to surround BioBricks, as well as the plasmids used to transform them. For a graphical representation of of the process, please click [http://ginkgobioworks.com/support/BioBrick_Assembly_Manual.jpg here]. A powerful online database provides information and characterization of all of the BioBricks in the Registry and uses the wiki format (the same one used in wikipedia) which encourages others to edit content directly on the page. Below are list of parts that were used/created for this project.

Parts used to characterize and build our final project

| Component | Part/Accession # | Base Pairs | Plasmid | Resistance | Well |

| RBS-34 | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0034 BBa_B0034] | 12 | pSB1A2 | Ampicillin | plate 1, 2M |

| Cph8 | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I15010 BBa_I15010] | 2,238 | pSB2K3 | Kanamycin | N/A |

| RFP | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_J04051 BBa_J04051] | 720 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| OmpR (E. coli) | [http://partsregistry.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_K098011 BBa_K098011] | 720 | pSB1T3 | Tetracycline | N/A |

| OmpR (R. sphaeroides) | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227010 BBa_K227010] | 720 | New | New | New |

| Terminator | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_B0015 BBa_B0015] | 129 | pSB1AK3 | Ampicillin and Kanamycin | plate 1, 23L |

| RBS +OmpR(sph) + Terminator

includes prefix and suffix | sequence

[http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227011 BBa_K227011] | 875/916 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | synthesized |

| OmpC promoter | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_R0082 BBa_R0082] | 108 | pSB1A2 | Ampicillin | plate 1, 16K |

| puc promoter | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227007 BBa_K227007] | 651 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | New |

| puc BA | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227006 BBa_K227006] | 336 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | New |

| puc B | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227005 BBa_K227005] | 156 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | New |

| puc A | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227004 BBa_K227004] | 165 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | New |

| OmpC promoter+pucBA | sequence

[http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227008 BBa_K227008] | 492/539 | pSB1k3 | Kanamycin | synthesized |

| Green Fluorescent Protein | [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_E0240 BBa_E0240] | 876 | pSB1A2 | Ampicillin | plate 1, 12M |

Plasmids used to create and characterize our project

| Plasmid | Base Pairs | Resistance | Copy Number |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB1A2 pSB1A2] | 2,079 | Ampicillin | high |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB1K3 pSB1K3] | 2,206 | Kanamycin | high |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB1A3 pSB1A3] | 2,157 | Ampicillin | high |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB2K3 pSB2K3] | 4,425 | Kanamycin | variable |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:pSB1T3 pSB1T3] | 2,463 | Tetracycline | high |

| pRKCBC3 | ~11.5kb | Tetracycline | 4 |

Parts submitted to the Registry of Standard Biological Parts

| Part/Accession #Component | Component | Type | Base Pairs | Plasmid | Resistance |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I15010 BBa_I15010] | Cph8 (planned resubmission) | Coding | 2,238 | plasmid | Resistance |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227004 BBa_K227004] | puc A | Coding | 165 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227005 BBa_K227005] | puc B | Coding | 156 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227006 BBa_K227006] | puc BA | Coding | 336 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227007 BBa_K227007] | puc promoter | Regulatory | 651 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227008 BBa_K227008] | ompC+PucBA (synthesized) | Composite | 492 | pSB1AT3 | Ampicilin,Tetracycline |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227009 BBa_K227009] | PucPromotor+GFP | Composite | 1377 | pSB1A2 | Ampicilin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227011 BBa_K227011] | RBS34+OmpR(sph)+Term (synthesized) | Composite | 875 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227012 BBa_K227012] | RBS34+OmpR(sph)+Term+OmpC+PucB/A | Composite | 1375 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227013 BBa_K227013] | ompCpro + GFP | Composite | 992 | pSB1A2 | Ampicilin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227014 BBa_K227014] | pucpro+pucBA | Composite | 1035 | pSB1K3 | Kanamycin |

| [http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_K227015 BBa_K227015] | RBS34+OmpR(sph)+Term+OmpC+GFP | Composite | 1875 | pSB1A2 | Ampicilin |

pucB/A

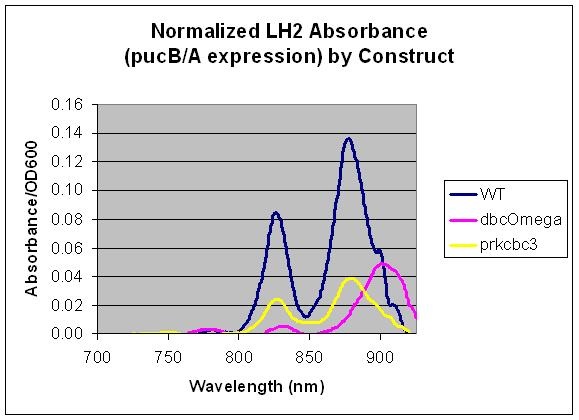

pucB/A are the genes that code for the beta and alpha subunits of the light harvesting complex LH2. Here, we measured the expression level of pucB/A from the puc promoter in the genome vs. on a low copy plasmid, pRKCBC3. This data allows us to utilize pucB/A as a reporter gene for expression from promoters, in complement to its role in cellular growth.

Method

Relative LH2 expression in R. sphaeroides 2.4.1, R. sphaeroides DBCΩ and R. sphaeroides DBCΩ pRKCBC3 grown anaerobically in the dark

Growth conditions: -Cultures grown in the dark at 34° C, shaking at 160 rpm - R. sphaeroides 2.4.1 -15 ml culture in polystyrene tube -15ml M22 was inoculated with 1ml inoculant with OD600nm = 0.270 - OD600nm (Volume) = 0.270 -Culture was allowed to grow 19hrs - R. sphaeroides DBCΩ -15 ml culture in polystyrene tube -15ml M22 was inoculated with 865ul inoculant with OD600nm = 0.312 - OD600nm (Volume) = 0.270 -Culture was allowed to grow 19hrs - R. sphaeroides DBCΩ pRKCBC3 -10 ml culture in polystyrene tube -10 ml M22 tet 5ug/ml was inoculated with loop of R. sphaeroides DBCΩ pRKCBC3 and capped with rubber stopper -Culture was allowed to grow for 3 days so that density was high enough to get a good reading

Analysis:

Cultures were removed from the incubtor and placed on ice to slow changes in cellular composition. 1 ml was extracted from each culture and a UV-vis absorption spectra of the culture was taken from 300-950 nm.

The optical density of the cultures at 600nm was used to normalize the absorption spectrum by division by this value. Background subtraction of spectrophotometer data was performed in Origin 6.1 Software. A ten-point baseline was created by a "positive peak" algorithm then modified to approximate the scattering curve that falls as the inverse fourth power of wavelength.

Results

Conclusion

This data indicates that pucB/A can be utilized as a reporter gene as the LH2 absorption bands at 800 and 850 nm are not present in the LH2 deficient mutant DBComega. Furthermore, changes in the expression conditions of pucB/A are reflected on the absorption spectrum. In this case, expression is higher when the genes are expressed from the puc promoter within genomic DNA than on plasmid pRKCBC3, despite the fact that pRKCBC3 is maintained at 4-5 copies in a cell.

Puc Promoter

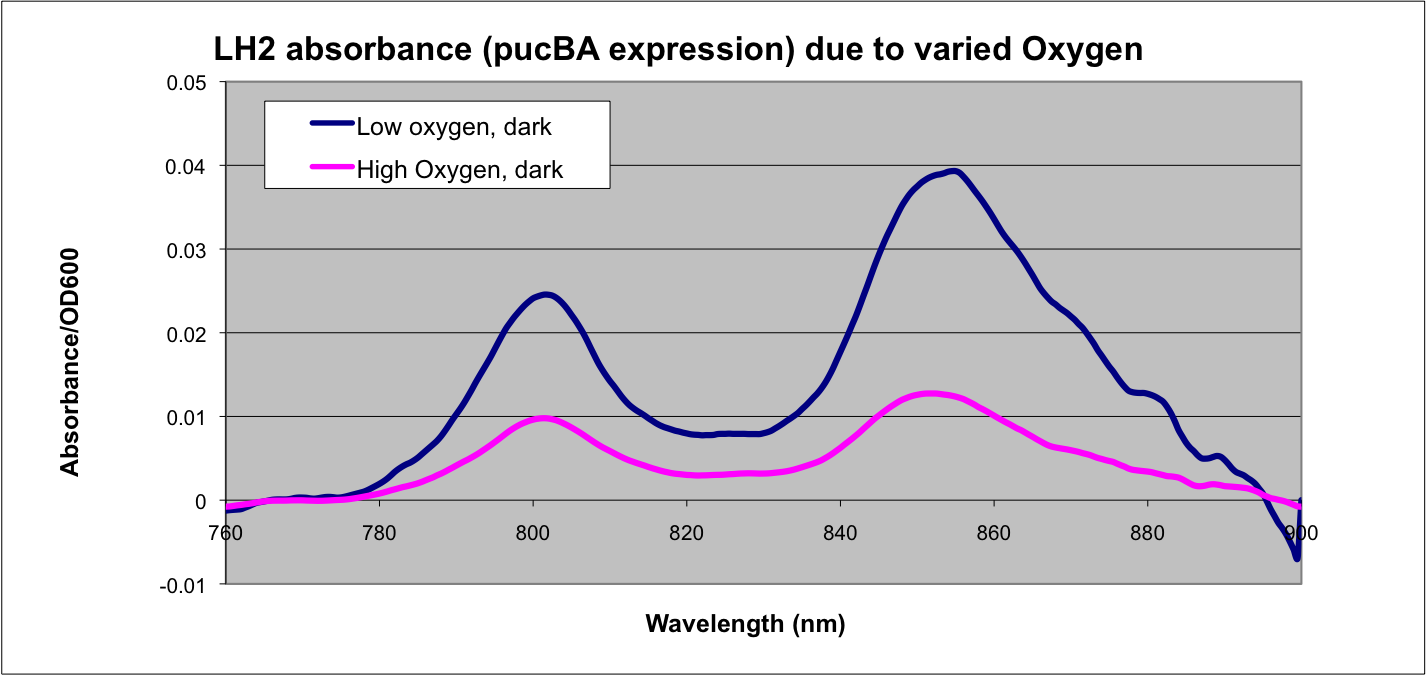

More absorption of light at the LH2 spectra peaks normalized to culture OD corresponds with more transcription and vis versa.

Method

Cultures were grown in the dark at 34° C, shaking at 160 rpm. The anaerobic test condition was established by inoculating a 10 ml culture tube with 10 ml M22 tet 5ug/ml with a loop of R. sphaeroides DBCΩ pRKCBC3 and capped with a rubber stopper. The aerobic test condition was established by innoculating a 10 ml culture tube with 5ml M22 tet 5ug/ml with a loop of R. sphaeroides DBCΩ pRKCBC3 and covered with vented cap- the vented cap and relatively low culture volume left significant headroom in the culture for oxygen exchange. Oxygen tension was not able to be quantitatively measured due to the nature of the experiment

For measurement of pucB/A expression from the puc promoter:

Cultures were removed from the incubtor and placed on ice to slow changes in cellular composition. 1 ml was extracted from each culture and a UV-vis absorption spectra of the culture was taken from 300-950 nm.

The optical density of the cultures at 600nm was used to normalize the absorption spectrum by division by this value. Background subtraction of spectrophotometer data was performed in Origin 6.1 Software. A ten-point baseline was created by a "positive peak" algorithm then modified to approximate the scattering curve that falls as the inverse fourth power of wavelength.

Results

Conclusion

This data matches the literature for expression from the puc promoter at different oxygen tensions and as such confirms the assumptions that we have made in modeling our system.

See: Braatsch et al. 2002

Modeling the Gene Regulatory Network

References

1. Alon, Uri. Introduction to systems biology and the design principles of biological networks. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall, 2006.

2. Bower, James M. Computational Modeling of Genetic and Biochemical Networks (Computational Molecular Biology). New York: M.I.T. PRESS, 2001.

3. System modeling in cellular biology from concepts to nuts and bolts. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 2006.

Simulation Equations

Nonlinear least-squares estimation of LH2 saturation curve

Exponential response curve for mutant LH2 saturation coefficients

Figure ?

Relative growth of DBComega to WT in Flask 2 at OD 600

This data illustrates the contribution of LH1 to growth relative to that of LH2

Problem: In a typical reactor, cells at the surface absorb more than enough light to saturate their

photosynthetic apparatus, transmitting less energy to deeper layers. Cells operating past the saturation point

waste incident photons by non-photochemical quenching and possibly undergo photodamage. For wild type cells, the

“saturation curve” is assumed to be approximately the same for all cells in all layers, regardless of their

incident light intensity. This means that layers of cells on the exterior of the reactor nearest a light source

receive an overabundance of photons and in turn block the interior layers from receiving enough light. In an

optimal reactor, all layers would operate near their respective saturation points to maximize the photosynthetic

channeling of incident light energy. The total saturation curve for wild type R. Sphaeroides was fit with a nonlinear least squares regression of the

form in Equation A. Data points were generated from calculating absorbance as the negative logarithm of the ratio

of the absolute irradiance detected on the next layer to incident absolute irradiance on a layer of cells. A

logistic form was chosen to account for the diminishing returns to absorption of further photons past a threshold

operating capacity of the photosynthetic apparatus. (1)

Simulating our Mutant's advantage in a Bioreactor

For our mutant cells, the LH2 saturation curve for each layer scales as a function of light intensity. This

predicted behavior in the mutant is due to negative regulation of LH2 complex production as incident light

intensity increases. The scalar of the magnitude of the saturation curve was altered according to a predicted

exponential curve of LH2 production in repsone to changes in incident light. It was assumed that the system could

vary expression levels such that at high light intensities, the saturation curve is scaled to 25% of that of the

wild type. At low light intensities, LH2 production was assumed to have the potential to be up-regulated to 150%

of wild type expression levels. The advantage this mutant would confer stems from the adaptive nature of the saturation curve heights. Cells

receiving the most light on the outside of the bioreactor saturate at low absorption levels. This allows more

light to transmit to further layers, which have elevated saturation curves due to lower incident light.

Assumptions:

- Light intensity at next layer is given by transmittance from previous layer (assumes no backscattering).

- Total energy funneled to photosynthetic pathways is estimated as the sum of light absorbed by each layer. This

generalizes to the optical density measurement of cell culture density. - The constant wild type saturation curve inherently includes both LH2 and LH1 contributions to absorbance. The

mutant's variable saturation curve only accounts for LH2 absorbance, since this is the only complex under the

light-sensing regulation. To account for the component of absorbance provided by LH1, the proportion of total

optical density due strictly to LH1 was investigated by comparing the growth of wild type and LH2-knockout

(dbcOmega) cultures. It is evident that by day three the proportion of Optical Density accounted for by LH1

absorption converges to a value near 0.2. In other words, at the phase the layers of cells have grown in the model,

20% of total optical density can be attributed to LH1. To account for this, the absorption in the mutant was

divided by the factor (1-0.2) = 0.8. Then, the total optical density of the mutant cultures reflects total

absorption by both LH1 and LH2.

Model Assumptions

- Light intensity at next layer is given by transmittance from previous layer (assumes no backscattering).

- Total energy funneled to photosynthetic pathways is estimated as the sum of light absorbed by each layer. This

generalizes to the optical density measurement of cell culture density.

- The constant wild type saturation curve inherently includes both LH2 and LH1 contributions to absorbance. The

mutant's variable saturation curve only accounts for LH2 absorbance, since this is the only complex under the

light-sensing regulation. To account for the component of absorbance provided by LH1, the proportion of total

optical density due strictly to LH1 was investigated by comparing the growth of wild type and LH2-knockout

(dbcOmega) cultures. It is evident that by day three the proportion of Optical Density accounted for by LH1

absorption converges to a value near 0.2. In other words, at the phase the layers of cells have grown in the model,

20% of total optical density can be attributed to LH1. To account for this, the absorption in the mutant was

divided by the factor (1-0.2) = 0.8. Then, the total optical density of the mutant cultures reflects total

absorption by both LH1 and LH2.

- The model was revised upon gathering optical density data from the five layers of the bioreactor setup. (See

Results Figure 2a.) In the wild type, the optical density of the first flask of cells was much lower than

predicted, a phenomenon that was attributed to photodamage of the cells due to exposure to a large quantity of

light past the saturation point of the LH2 complexes. In the optical density data for the flasks, both the

dbcOmega knockout and the wild type logistically grew to an absorbance value of 1. This gave reason to put a hard

limit of 1 on the first flask's potential optical density. Any light left over from this cutoff was transmitted to

the next layer, as evidenced by in the increased growth of the second wild type flask in the Optical Density data. - The response curve for the coefficient of saturation for the mutant due to changes in light intensity was modeled

as an inverse exponential form. In other words, the system reacts to increasing light intensity by exponentially

tapering the coefficient of saturation.

Saturation curve: Absorbance as a function of incident light intensity.

The coefficient changes with intensity in the mutant only.

Assumptions:

- Light intensity at next layer is given by transmittance from previous layer (assume no backscattering).

- Total energy funneled to photosynthetic pathways is estimated as the sum of light absorbed by each layer.

type here1

type here2

type here3

References